by John Clayson

We have gathered together stories and photographs which illustrate life down the years at Grantham North signal box. There are reports from the local newspaper The Grantham Journal (which continues in publication today) and we’ve searched far and wide for photographs. Most importantly, people who worked on the railway at Grantham have kindly shared their personal recollections of the job and of the people they worked with.

We are presenting what we have in chronological order. Material is still coming to light and we will slot new items in as they are discovered. If you have anything which adds to the story of Grantham North box please let us know.

_________________________________________________________

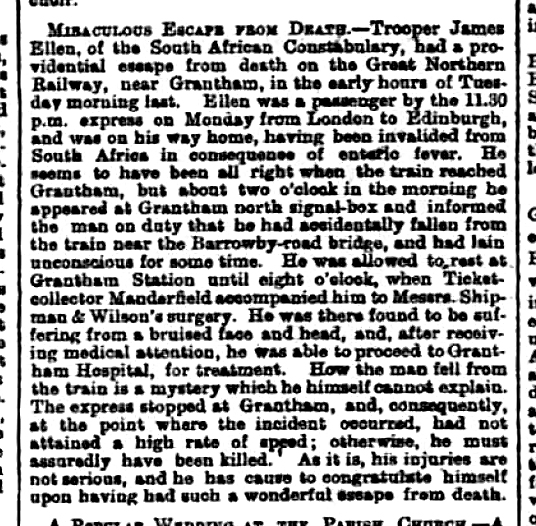

Our first story is from The Grantham Journal of 29th September 1901 and is the tale of an unexpected visitor in the early hours of one morning …

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

________________________________________________________

The Grantham Railway Disaster of September 1906

A few minutes after 11pm on the night of Wednesday 19th September 1906 a London to Edinburgh sleeping car and mail train, which had been due to stop at Grantham, ran at speed through the station against the signals. At Grantham North signal box the points were set towards the Nottingham line because, shortly before the express was due to arrive, a goods train from Leicester had passed across the junction. Consequently the Scotch express took the diverging line at Grantham North well in excess of the safe speed. The ensuing high speed derailment on the bridge and embankment beyond the box, and fires which subsequently broke out in the wreckage, took 14 lives including those of the locomotive crew.

During the minute or so that it took for events to unfold that night the staff on duty at Grantham, in the signal boxes and at the station, were simply bystanders as the train sped towards them out of the darkness. They bore no responsibility for the accident and they were powerless to prevent it, but they responded bravely to the need of the hour as the terrible consequences became clear.

From The Grantham Journal of 22nd September 1906

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

What caused the accident?

There has been much conjecture as to the cause of this tragedy, the second of three fatal high speed derailments which took place on railways in England in a period of a little over a year. They occurred at Salisbury on 1st July 1906, at Grantham on the following 19th September, and at Shrewsbury on 15th October 1907.

The Board of Trade’s official enquiry into the Grantham accident was led by the government’s Inspecting Officer of Railways, Lt. Col. Pelham George von Donop of the Royal Engineers. The published report of such an enquiry would normally finish with a conclusion as to the cause of an accident and recommendations to prevent, or reduce the risk of, recurrence. However in the case of Grantham Lt. Col. Von Donop felt unable to determine the cause of the accident. In his report’s lengthy Conclusion he weighs up a range of alternative causes suggested by sometimes contradictory evidence, suggesting which were more likely than others. He offers no definitive answer to the fundamental question of why the train did not stop at Grantham as it had, perfectly normally, the previous night with the same footplate crew aboard the same locomotive.

Lt. Col. von Donop’s report is available on the Railways Archive website here.

During the enquiry much attention was focussed on the train’s brakes, and whether they were applied in the seconds before the derailment. The train was equipped with a power-operated braking system known as ‘the continuous automatic vacuum brake’ which was designed to ‘fail safe’. At Peterborough the locomotive had been changed and an additional vehicle was added at the rear of the train. Significantly, in his report Lt. Col. von Donop discounted the possibility that lapses in procedure when reconnecting and testing the brakes at Peterborough could have rendered the vacuum brake equipment inoperative on all the carriages of the 12-coach train. He asserted that the driver would not have been able to release the brake and start the train unless the proper procedure had been followed.

Recent review of available evidence tends to confirm a view, formulated by railwaymen at Grantham who were closest to the event, that a potential combination of circumstances did exist which could result in the train starting out from its Peterborough stop with the vacuum brake inoperative. If the driver then failed to perform a 'running brake test' once on the move after leaving Peterborough he would be unaware of the perilous situation until, having accelerated to around 60mph on the five-mile descent from Stoke summit, the brake failed to respond to his initial application on the approach to Grantham. The only brakes then available to him and his fireman were those on the locomotive's four driving wheels and on its six-wheeled tender. With the junction points at Grantham North set to divert the train abruptly from the Main line, the train’s fate was sealed.

There were two guards, but the enquiry found that neither was sufficiently alert to the train's progress and its failure to slacken speed until it was far too late for them to act by applying the hand brakes in their vans in support of the hapless footplate crew.

The locomotive crew could not have known that the junction points were set for the divergent line to Nottingham. Right until the first violent lurch they would likely have believed that their train would run through the signals set at danger, eventually to stop beyond the station but still on the main line. No one would be harmed, though there would be an investigation to face.

The absence, according to the evidence of all witnesses, of a warning whistle from the speeding runaway is, however, puzzling in these circumstances.

For further reading:

- The Grantham Rail Crash of 1906 by Harold Bonnett (Bygone Grantham, 1978 ISBN 0 906338 05 0)

- Great Northern News (GNN) No.149 (Sept/Oct 2006) pages 149.11 to 149.23, The Grantham Accident, 19th September 1906 [originally published in 1982, revised and illustrated]; supporting information and correspondence in GNN Nos. 150, 151, 152 & 153. Published by The Great Northern Railway Society.

- The Railway Magazine Vol.152, No. 1,265, September 2006, pages 22-27 Grantham - The mystery solved, 100 years on? by Nick Pigott

- The Railway Magazine Vol.152, No. 1,266, October 2006, pages 25-26 Grantham Crash: The real 'mystery' is why the most obvious question was never asked! by Nick Pigott

Inquests and an Enquiry

Several of Grantham’s railwaymen were key witnesses at two separate formal proceedings in the days that followed the accident.

The Inquests

Two Inquests were held at the Grantham Coroner’s Court. Their purpose was to confirm the identity of the victims and establish how they died.

The first inquest, held in the in the Session’s Hall (courtroom) at the Grantham Guildhall, opened on Friday 21st September. Having confirmed the identities of all the victims who died in the wreckage it was adjourned to Tuesday 25th September, when eye witnesses of the accident and expert witnesses were called and the jury reached its Verdict.

A second, much shorter, inquest was held before a new jury on Friday 19th October following the deaths of two injured passengers.

The Coroner for the Borough of Grantham was lawyer Aubrey Henry Malim, himself the son of a Grantham solicitor. Inquests were (and still are) held in public and hence, in the circumstances of railway accidents involving multiple fatalities, they were likely to be widely reported in the newspapers. In those days an inquest jury consisted of 12 men, who qualified for jury service by being either a landowner or the head of a household; women first became eligible for jury service in 1919.

The Board of Trade Enquiry

An Enquiry was held by the Board of Trade into the cause of the accident. The Regulation of Railways Acts empowered The Board of Trade, a department of government, to investigate, in the public interest, certain categories of accident on the railways.

The Enquiry, chaired as noted above by Lt. Col. von Donop, son of a Royal Navy vice Admiral, had sittings at Grantham Station on Monday 24th and Tuesday 25th September, and in London on 26th October. The Enquiry was held in private, but the outcome was a published Report.

Richard Scoffin, GNR Signalman, Grantham North signal box

The harrowing experience of the accident was only days behind the men who had been most closely involved when they were called to give evidence, in very formal settings, of what they had witnessed during those brief seconds when the mail and sleeper train approached, tore through the station and was wrecked a few yards beyond the North box.

The men on duty in the signal boxes, whose job it was to be especially observant of passing trains, were seen as vital witnesses in the search for answers to the mystery of why the train failed to stop at the station.

Ultimately neither the Verdict of the Coroner’s Court nor the Board of Trade Inspecting Officer’s Report attributed any blame for the accident to the actions or the judgement of the signalmen at Grantham on that fateful night. Some recommendations were made in relation to local signalling practice, but all the men were found to have performed their duty professionally, according to their training, and following rules and procedures in force at the time.

However, from press reports of the inquest it's clear that the signalman at Grantham North, Richard Scoffin, was taken to task by both the Coroner and a member of the jury. They suggested that Scoffin had been negligent by not re-setting the junction points to the Main line immediately after the goods train from Leicester had passed, and that had he done so the derailment would not have happened.

Both sets of proceedings exemplified the class structure of Edwardian Britain. Asking the questions were men from privileged backgrounds, well educated and very much at home with the formalities. Answering them were ordinary working men who probably felt, at best, ill at ease, and at worst intimidated.

Richard Scoffin was born in 1869 at Algarkirk near Boston in Lincolnshire, the son of a platelayer on the Great Northern Railway. By 1891 he had become a signalman at, or near, Waltham on the Wolds in Leicestershire. At the time of the Grantham accident Scoffin, aged 36, had nearly 16 years’ experience as a railway signalman.

Scoffin was an important witness at both the Inquest and the Enquiry. He gave evidence on three days - on 24th September at the Enquiry at Grantham Station, on 25th September at the Inquest at Grantham Guildhall, and again at the Enquiry on 26th October in London.

The enquiry found Scoffin blameless with regard to the accident, but at the Coroner’s inquest he was repeatedly questioned about why the points at the Nottingham line junction were set for the diverging route. Questions were put by the Coroner himself and he was also cross-examined ‘at great length’ by a member of the jury, a Mr J. McIntosh (possibly John McIntosh, a local accountant). Both men inferred that Scoffin was partly responsible for the accident through negligence, because the junction points remained set for the Nottingham line after the goods train had passed.

The same line of questioning continued when two of the GNR's most senior officers were called to give evidence. Company solicitor Richard Hill Dawe and William Henry Hills, the Superintendent of the Running Department (and thus responsible for the training and examination of the company’s signalmen), both spoke forcefully in Scoffin’s support.

At one point the Coroner asked Hills, “I take it that you think … that he [Scoffin] was acting strictly in accordance with his duty?” Hills replied, “Absolutely so. I should say he was working as a properly-qualified and good signalman would do.”

The effect of the horrific accident followed by the gruelling enquiry and court appearances appear to have affected Richard Scoffin to the extent that he could no longer follow a career in signalling. The company transferred him to a different department of the railway as an assistant inspector, though he continued to live and work at Grantham.

Here is the coverage of this part of the inquest proceedings as reported in The Grantham Journal, followed by the reporting of the Summing Up and the Verdict:

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

_____________________________________________________________

Richard Scoffin is mourned by friends and colleagues

In February 1914 Richard Scoffin succumbed to pneumonia at the age of only 44. Below is an extract from the report of his funeral in The Grantham Journal, from which it is clear that he was highly regarded, both among the town’s railway community and by his employer, the GNR. His coffin was borne by six local signalmen.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

_______________________________________________________________

Fred Dobney, Divisional Inspector of Signals at Grantham, retired in September 1925. In this article his career of 50 years on the railway is recalled. There is a poignant reference to the 1906 accident. Mr Dobney covered Richard Scoffin’s shift at Grantham North box the night after the disaster.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

_________________________________________________________________

In June 1929 North Box signalman William Pearson retired.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

_________________________________________________________________

In late October 1931 alert railwaymen, including signalman Ernest Lancaster on duty in Grantham North box, reported a fire in a timber yard adjacent to the railway.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

__________________________________________________________________

William E. Allen was one of three Inspectors who retired on 31st March 1933. Born in 1871 at Bourne, he had been a Telegraph Lad then Signalman at various locations on the GNR including both the South and the North Boxes at Grantham. He was promoted to Inspector in 1904. In 1911 he and his family lived at No.9 Station Road, a house which used to stand right opposite the station entrance.

To fill one of the vacancies caused by the retirements Signalman Lancaster, mentioned above, was promoted from the North Box to Inspector.

The careers of these two men demonstrate the path from the senior signalling grades into management.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

__________________________________________________________________

In March 1934 Frederick William Smith retired as relief signalman at Grantham, a position he had held since 1910. In a final echo of the 1906 accident Mr Smith is listed, in the February 1914 report above, among the bearers at Richard Scoffin’s funeral.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

________________________________________________________________

Grantham North box on film, July 1937

The following pictures are taken from a film thought to have been made on 5th July 1937 to record the passage of the first streamlined Coronation non-stop London to Edinburgh service.

We don’t know the names of the Signalman and Telegraph Lad who featured in the film, but they may well be among the men whose names are listed in the October 1939 ‘Return of Staff’ noted below.

From a film shot by Walter Lee. © Lincolnshire Film Archive

From a film shot by Walter Lee. © Lincolnshire Film Archive

From a film shot by Walter Lee. © Lincolnshire Film Archive

__________________________________________________________

Grantham North Box Signalmen and Telegraph Lads, October 1939

In October 1939 a ‘Return of Staff’ was compiled for Grantham Passenger Station. It lists employees by name with their job and place of work, dates of birth, their date of entry to the railway service and their rate of pay.

Here are the men who were working at Grantham North signal box:

Signalmen:

John William Bland

♦ born 13/12/1876; entered service 4/12/1892; paid £3 15s per week

Wadkin Hare

♦ born 3/7/1887; entered service 1/1/1902; paid £3 15s per week

Harold Bullimore

♦ born 8/7/1886; entered service -/-/1900; paid £3 15s per week

Relief Signalman:

James Palmer

♦ born 17/2/1878; entered service 17/10/1892; paid £4 per week

Telegraph Lads:

Joseph Raymond Laughton

♦ born 25/10/1919; entered service 1/11/1937; pay £1 15s per week

Ernest William Atter

♦ born 6/12/1919; entered service 14/3/1938; pay £1 15s per week

Stanley Brackenbury

♦ born 14/2/1921; entered service 30/1/1939; pay £1 10s per week

Kenneth Edward Nicholls

♦ born 14/10/1921; entered service 15/5/1939; pay £1 10s per week

The signalmen at the North Box were paid £3 15s per week, the highest rate of all the Grantham boxes. By comparison, a signalman’s pay at Grantham South Box was £3 10s, at Grantham Yard Box was £3 5s and at Barrowby Road was £2 15s.

The information above was kindly submitted by correspondent Strang Steel to the Returning to Grantham thread on the LNER Forum here (commencing on page 70).

_____________________________________________________________

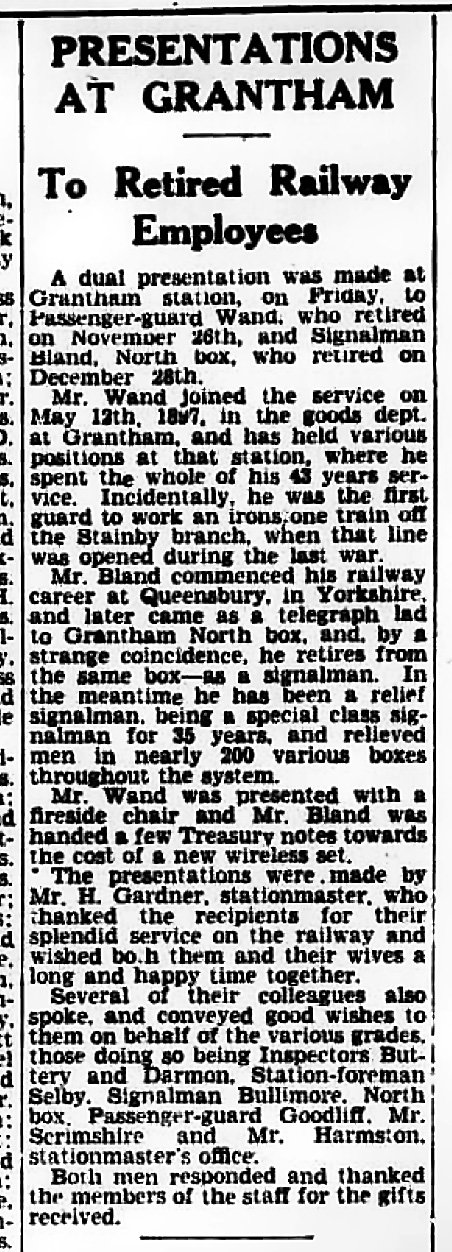

Special Class Relief Signalman John William Bland (noted above) retired on 28th December 1940. He was born at Londonthorpe near Grantham and worked at Bingham and Retford during his career.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

_____________________________________________________________

In January 1954 Harold Scampion, Grantham’s Stationmaster, spoke to the local Round Table about the intensive traffic dealt with at the North box.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

______________________________________________________________

Staff at Grantham North Box 1959-1962

Former Grantham signalling staff have helped to compile a list of the signalmen and telegraph lads who worked the North Box:

Regular Shift Signalmen / Telegraph Lads

♦ Albert Eldridge / Dennis Gray (see first photograph below)

♦ Wilf Ogden (Mayor of Grantham in 1961-62) / Walter Howe

♦ Bernard Knipe / Derek Steptoe

Rest Day Relief

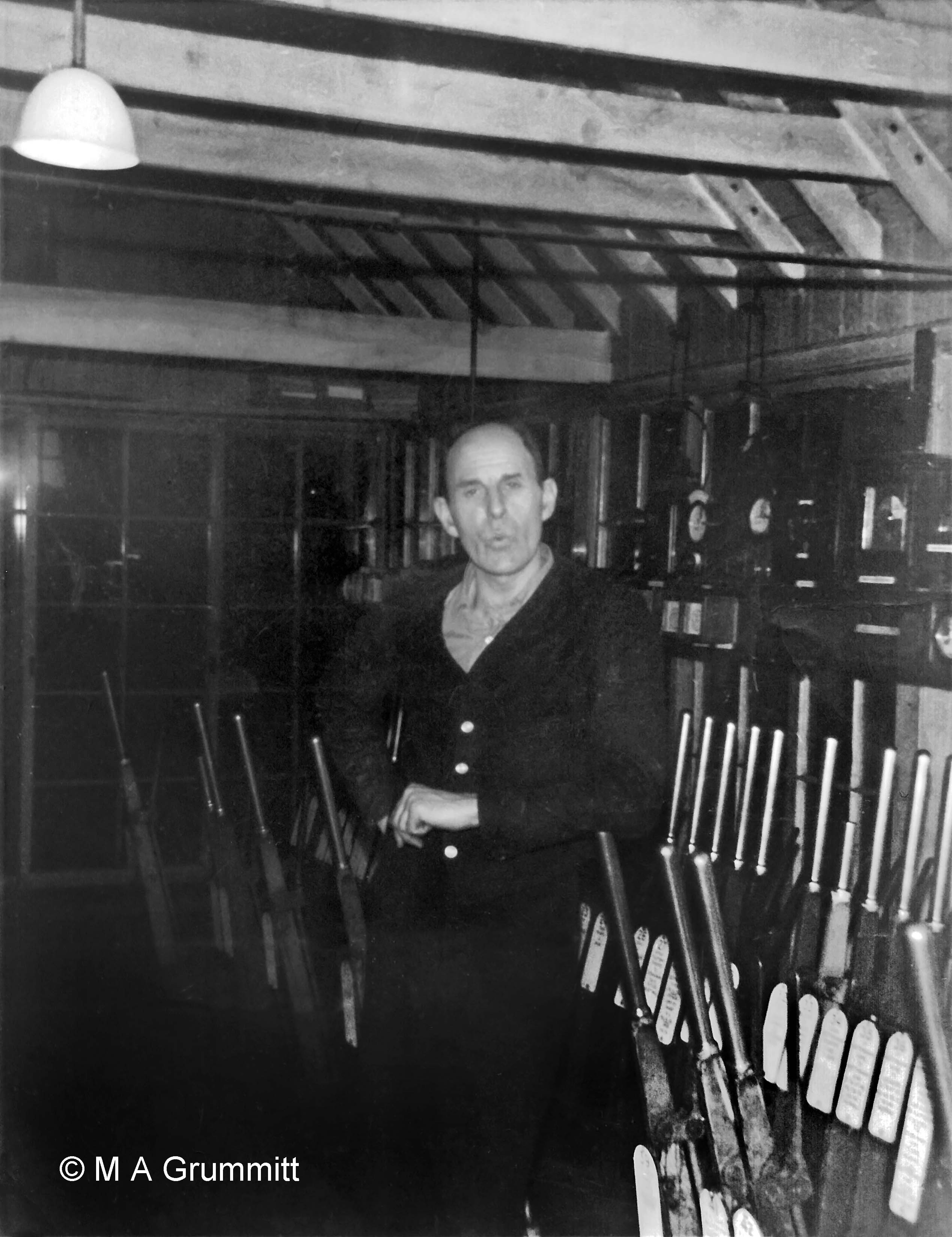

♦ Albert Steptoe (see second photograph below) / Mick Grummitt

General Purpose Relief

♦ Les Keily / Arnold Bullock

John Pegg told me that the wooden armchairs in each box were usually placed close to the fire or stove, especially in winter. The joints dried out and became loose, so they often needed to be ‘reinforced’ to hold them together. Strands of signal wire were wound round the legs and arms and tightened, like a tourniquet, to keep the chairs in one piece.

Photograph by Cedric A. Clayson.

Photograph by Mick Grummitt.

Mick Grummitt was RDR tele lad (Rest Day Relief Telegraph Lad) at Grantham North between 1959 and 1962. He worked regularly with Albert Steptoe at Grantham North and Grantham South. Mick also covered Westwood Junction, Spital Junction and Crescent Junction boxes at Peterborough as RDR tele lad. Mick started on the railway as a Lad Porter at Great Ponton station.

Staff at Grantham North Box 1967-1969

Ian Moir was a telegraph lad in North Box from 1967-69. He writes "There were only two lads at North Box when I was there so we worked 12hr shifts, which meant I worked with all three signalmen. The signalmen were Albert Eldridge, Bernard Knipe and Les Keily."

The Night 'The Mail' Didn't Quite Stop

Mick remembers an incident when he was on duty one night shift with Albert Eldridge in the North Box at Grantham.

A northbound sleeper and mail train called at the station each night. On this occasion it was running about 20 minutes earlier than usual. Having a powerful Deltic diesel-electric locomotive that night the driver was gaining on the schedule. At the North Box they were awaiting its arrival in the main line platform.

The phone rang. It was the signalman at the South Box. “This one’s not going to stop tonight, Albert.” As it passed his box the South Box signalman had seen that the train was travelling far too fast to stop in the platform.

The Nottingham line junction points at the North Box were set for the Main line, so Albert was able swiftly to change the signal at the platform end from red to a cautionary yellow. They watched as the Deltic and its sleeping cars ran at speed through the station, past the box and off into the night towards Barrowby Road box, with sparks streaming from the brake blocks.

The phone rang again. It was Barrowby Road. “I’ve got a train on the Main line stopped outside the box.”

“Tell him the station’s back here.”

The driver came on the phone from Barrowby Road. He hadn’t driven Deltics very often and he had completely mistimed his brake application. The train was carefully ‘set back’ along the Main line and into the platform, a distance not far short of a mile.

Thanks to the warning from the South Box, and Albert’s alert response, no signal was passed at danger, an event that would have required official investigation.

Not only that. Receiving the yellow signal for the Main line spared the driver the anxiety that the points might be set for the Nottingham line. Had this been the situation it would have repeated the circumstances of the fatal high speed derailment of 1906 noted above, possibly with even more disastrous consequences.

In fact, because it had previously been running early, the sleeper left Grantham just about on time that night, and no-one but those immediately involved was any the wiser.

Forward to A visit to Grantham North signal box in August 1963

Back to the Grantham North signal box index page

Copyright note: the article above is published with the appropriate permissions. For information about copyright of the content of Tracks through Grantham please read our Copyright page.