by John Clayson

Introduction

This page began as a couple of press cuttings from the early years of The Grantham Journal nearly 160 years ago, reporting on a royal visit to Grantham of just a few minutes' duration.

However, the more I discovered about the train journey made by Queen Victoria and her family in early September 1855 from King's Cross to Edinburgh (and onward the following day to Banchory), the more the story brought into focus aspects of Victorian society, and the more it shone a light on the risks being run from day to day by the railway companies with their employees' and their passengers' lives.

We draw upon the fascinating archive of Victorian journalism in the British Library to show how a short stopover by Queen Victoria and the Royal Family drew the crowds to Grantham station. We go on to reveal the hazards even the royal family faced when travelling by train in the 1850s. The story is an intriguing insight into the safety culture on the railway 160 years ago.

The story has lengthened considerably, but I hope readers will find it as fascinating to follow as I have to research.

________________________________________________________________________

Background

On 6th September 1855 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert paused at Grantham station on their annual journey to Balmoral Castle in the Scottish Highlands.

For several years the royal family had been using Britain's railways to travel to and from their autumn holiday at Balmoral. In those early days of long distance rail travel the Royal Train, like any other, stopped for a few minutes at frequent intervals while the locomotive took water, or was changed, and the carriage axles were greased.

In 1854 the Great Northern Railway's new main line between Peterborough and Retford was used for the first time, but no stop was made at Grantham. However, in 1855 Grantham was selected for a stopover slightly longer than required for servicing the locomotive and the carriage axles so that their majesties could briefly meet a delegation of civic dignitaries, led by the Mayor. Such ceremonials took place at selected stopping points each year, and we think this was the first, and possibly the only, occasion when Queen Victoria made an official visit to Grantham.

In the following reports from The Grantham Journal we read of the elaborate preparations for the royal reception and of the spectacle enjoyed by the crowds that Thursday morning.

________________________________________________________________________

Preliminaries – the Royal Equerry arrives in town

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Does anyone know why there should be the reference about 'not mentioning' the former King’s Free Grammar School? Clearly it was a sensitive issue! It's interesting to note that in 1855 the station was beyond the town boundary.

________________________________________________________________________

Grantham Station’s First Royal Visit

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Despite appearances all was not well with the running of this Royal Train. As we will see, the Great Northern Railway staff accompanying the train were struggling to keep it on the move and maintain the reputation of the company. A few hours after the Grantham stop a tragic accident befell one of the GNR’s employees, as efforts to keep the train on schedule led to appalling risks being taken with the lives of the staff - with no small risk to the safety of the royal family themselves.

_________________________________________________________________________

The Royal Train and the Railway Companies

When Queen Victoria began to travel by train in 1842 it was the first time that a ‘private sector organisation’, to use a modern term, was entrusted so completely with the safety and wellbeing of a reigning monarch of the British Empire.

To convey the Queen and her family was the ultimate mark of prestige for a railway undertaking and nothing, it seemed, was left to chance by the railway companies. For that first journey, from Slough to Paddington by Great Western Railway, on the locomotive’s footplate were none other than Daniel Gooch, the GWR’s Locomotive Superintendent, and Isambard K. Brunel, its renowned Chief Engineer.

By working the Royal Train over much longer distances the GNR and its east coast partners had a lot to gain if the journey went well, but they also potentially had a lot to lose if problems arose. Timekeeping was seen as vital. A safe ‘on time’ arrival at Edinburgh meant everything in terms of prestige, publicity and attracting traffic from competitors. The companies which ran the rival west coast route to Scotland were more than ready to highlight late running with the Royal Train as an indicator of unreliable regular services.

The Great Northern Railway took the lead in managing the east coast lines’ Royal Train. In 1854 the northbound train was said to consist of ‘the Great Northern Company's suite of state carriages, with two or three ordinary first-class carriages for the attendants...’ (from The Manchester Courier, 9th September 1854). The journey to Edinburgh took in the GNR route from King’s Cross to just north of Doncaster, then the North Eastern Railway to Berwick upon Tweed, and the North British Railway thence to Edinburgh.

________________________________________________________________________

The Royal Train of 6th September 1855

The extract below relates to the northbound 1855 journey which, as described above, stopped for a few minutes at Grantham. It demonstrates the importance the east coast companies attached to ensuring that all went well on the day. (Note that the name of the GNR Locomotive Superintendent, Archibald Sturrock, is spelt as if the reporter wrote it phonetically, possibly having heard it spoken by the man himself in what may have been a strong Tayside accent.)

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

GNR Chairman Edmund Beckett-Dennison had a reputation as a tough and uncompromising man. At his death even the local Tory paper described him as ‘brusque in his manner, impatient to a degree of human vanity in all its ugly shapes, and with little trace of sentiment or poetry of any description’. Imagine the pressure his presence on this occasion imposed on the management and staff responsible for operating the train.

The ‘pilot engine’ in advance of the Royal Train and the ‘special engine’ in the rear were vital to ensure safety, given the operating rules then in place on the railways. The two engines created ‘space intervals’, zones guaranteed free of all other traffic, which advanced in front of and behind the Royal Train. As an additional precaution trains travelling in the opposite direction, and shunting and other operations near the line, stopped 30 minutes before the Royal Train became due. In effect, an advancing protective ‘bubble’ was established inside which the Royal Train travelled, insulated from risk of collision with ordinary traffic.

Such precautions were necessary because of the fundamentally unsafe ‘time interval’ signalling system then in use to control normal railway traffic (see our signalling history section here). It resulted in numerous collisions, especially as locomotives became more powerful and the weight and speed of trains increased without corresponding improvements in the effectiveness of braking systems. The railway companies were well aware of the hazards of the time interval system. The technology was available, in the form of the electric telegraph, to establish the much safer ‘space interval’ system of signalling and reduce risks for everyone travelling on the railway, not just the royal family. Until parliament forced the issue in 1889 some railway company directors preferred to maximise profits for shareholders rather than invest in safer methods of working their main lines. When the royal family might be at risk on their patch it was a different matter, however, and an improvised space interval system was put into practice!

_________________________________________________________________________

Trouble On Board

So, back to the GNR’s Royal Train on 6th September 1855. Early in the journey several of the wheel bearings were seriously overheating. The following newspaper report summarises the developing situation.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The above report is incorrect as to the location of William Haigh's accident, which took place a few miles north of Darlington.

_________________________________________________________________________

Inquest into the death of William Haigh

Here is a report of the Inquest into William Haigh's death.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The River Skerne is still crossed today by the East Coast Main Line at the site of the accident, which is about 150 metres east of the A1(M).

Note the denials by managers and supervisors that examiners were ordered to travel on the footboards, in contrast to the report in The Nottinghamshire Guardian quoted previously.

The carriages were maintained by the Great Northern Railway, and senior railway officers travelling with the train must have become more and more preoccupied with keeping the royal family on the move in an attempt to deliver them on time at their overnight stop in Edinburgh. It must have been an embarrassment to the company to have to ask the Queen to leave the GNR's Royal Saloon at Darlington.

William Haigh was aged 30. He and his family lived at 12 Bond Street in Doncaster. He was laid to rest in the parish of Christ Church, Doncaster on 9th September 1855.

There is an official report on the accident here. It concludes that the cause of the overheating of the axle bearings was a specially prepared batch of grease that had not been effectively tested in service and was 'too stiff'.

________________________________________________________________________

Mrs Haigh's Life Pension

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Today this £30 annual pension would be equivalent to about £28,000 pa.

_________________________________________________________________________

Here is a photograph of the royal family at Balmoral, taken a few days after the fateful journey described above took place.

Queen Victoria (1819-1901) is seated; Prince Albert, Prince Consort (1819-1861), is holding a hat and stick in his left hand; Prince Alfred (1844-1900); Prince Frederick William of Prussia (1831-1888); Princess Alice (1843-1878); Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (1841-1910), later King Edward VII; and Victoria, Princess Royal (1840-1901)

© The Royal Collection RCIN 2106411

_________________________________________________________________________

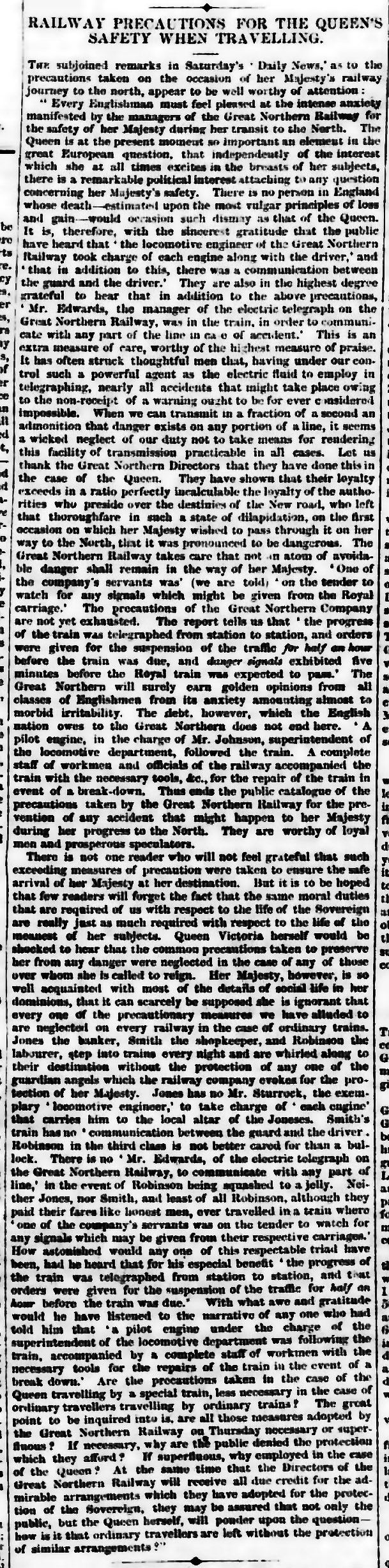

Railway Safety 'Double Standards'

It has already been observed that the early railways took elaborate steps to protect the royal family on their occasional journeys, while daily exposing thousands of ordinary travellers to risk of injury and death. This is pointedly addressed in the following article of September 1854, written following the publication of the precautions taken by the GNR to ensure the safety of the monarch on that year's royal journey to Deeside.

From The British Newspaper Archive

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Back to Events on the Railway at Grantham